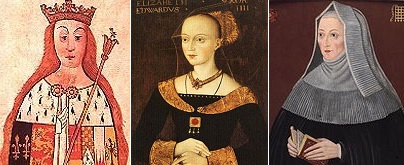

The Real White Queen – The Three Widows

A little while ago archeologists discovered what turned out to be the body of the last English King to die in battle. Richard III died in battle at Bosworth Field on 22nd August 1485 defending his Crown. His body was found beneath the car park of what is now a Leicester County Council Office. It seems likely that he was cut down by a blow to the back of the neck and skull by a halberd, which would have been fatal anyway, before being finished off on the ground in a brutal and efficient manner.

Richard is always said to have been the most notorious of English Kings and that comes from his reputation as a murderer of two small children, the “Princes in the Tower”. On the unexpected and premature death of his eldest brother, King Edward IV, in April 1483, the heirs to the throne were his brother’s two children, Richard’s nephews. They were 12 year old Edward, the lawful king despite not yet having been crowned, and 9 year old Richard.

Once they were in the Tower there were some swift and summary executions of people who might have stood up for their inheritance. The two young princes were swiftly accused of being illegitimate in a sermon preached outside St Paul’s Cathedral (an act of high politics and state in those days), and the good citizens of London, nobles and commons immediately “spontaneously” petitioned Richard to take the Crown as the last lawful heir of the late king, although what might have happened had this fortuitous event not occurred, what with northern Richard’s troops all over the capital, is a matter of speculation. Within a couple of days Richard had graciously accepted, and shortly afterwards he was crowned king. The illegitimacy of the two hapless princes was then confirmed by Act of Parliament in January 1483, an Act which made some very interesting allegations, to which I shall return another time.

The charge against Richard is very simple and very serious; that he put his nephews in the Tower of London, ostensibly to follow the tradition that this is where a king in waiting should be pending his coronation, but in fact as an act of imprisonment. There, by means unknown, but later alleged to be smothering, he had them put to death. Certainly, though their fate is unclear, they were never seen again.

Ricardians – the loyal followers of Richard – to this day maintain that he has been framed by later propagandists and spin doctors, including Shakespeare. They point to his reputation as a righteous law giver and ultra lawful supporter of his elder brother, the late King Edward. Indeed, there is no suggestion that he ever even remotely considered supplanting his brother and making a bid for the throne in his own right. Why, then, would he depose and murder his late brother’s children?

But all the circumstantial evidence, indeed, everything about the events of that year points to a very swift and efficient coup d’état in which the children were disposed of, both practically and legally, and the Crown taken. There is no getting away from the fact that the events of that summer point to a classic coup, from the moment King Edward died and Richard travelled south in full force to take possession his nephews.

This then, in outline, is the traditional history of the matter, and apart from the fact that the children were wrested from their mother, the widowed Queen Elizabeth, formerly Elizabeth Woodville, the history books make very little mention of any women in the story. In traditional history power is a commodity played for, won and lost by men.

A detective might say that there was a simple grab for power by an ambitious Richard. I suggest a better detective with a deeper insight into history and human nature might say: that is not the whole story; there is something missing. I believe that something is a matter which historians have overlooked – the role of women.

“The White Queen” has been doing rather well on BBC1 on Sunday nights. I have not really followed it but it looks very good, with plenty of costumes and plots and murders and bosoms and so forth, but for whatever reason I couldn’t get into it. It is, as I understand it, based on the best selling books by the author Phillipa Gregory, who has made a small and well deserved fortune bringing history to life.

In parallel to the glossy series, Ms Gregory has been allowed to do her own series explaining the period and the story in context straight to camera, called The Real White Queen And Her Rivals, also for the BBC. Unlike the “fictional” series, it had me gripped from the start. I have never really “got”, or followed the Wars of the Roses. I always found the books dull and I could never really get a sense of what was going on, or who was fighting who, or why.

In her own series, Ms Gregory suddenly and brilliantly took the veil from my eyes… so much so that I wanted to précis, if I could, the fascinating story she revealed. That this matter was not just about war and battle but something very unexpected. That the fate of the nation was decided not only by the men, but as much, if not more so, by three extraordinary women. Women who were if anything as brave, as ruthless, and probably more ambitious, tenacious and cunning in the pursuit of power than any of their male counterparts. They were by various degrees power seekers, diplomats, and one was suspected of witchcraft. They were all killers or potential killers, directly or by agents. They plotted together, and against each other. They were women who would make mafia bosses look like kindergarten teachers. If Gregory and some equally able modern historians are even half right, it is the story of these three women which turns what looks in historical terms like a loose jumble of often inexplicable tableaus seen through a glass darkly, into a cohesive, Technicolor, fascinating narrative.

Their names were

Anne Neville, daughter of the Earl of Warwick;

Elizabeth Woodville, from a wealthy but technically common, non noble family; and

Margaret Beaufort, a minor noble woman who was to shape English and Welsh history for ever.

First, some context which it is important to understand.

England in the middle and late 1400s was, of course, a feudal society. In this world, the country is run by a handful of the elite noble families. How many noble families who counted there were I couldn’t say. Maybe a hundred, maybe five hundred? I don’t know. However, the club was select, and access to it very hard to gain. Within it one may say that there were internal divisions and hierarchies. To take a crude analogy, there may be 90 or more professional football clubs in England and Wales; but there is a Premier League, and within that Premier League there are the super rich and elite clubs. This was a closed shop. Non nobles were not welcome. Admission to the club was not generally welcome.

To be a member of this elite class was to be aware that one’s chief aim was to protect and if possible enhance the family wealth and prestige, chiefly by increasing the amount of land owned and this was usually achieved by fortuitous and strategic marital alliances. Marriage was an exercise in familial alliance, not love. Women would rarely be expected to be consulted upon whom they would marry. Often in the case of important women of noble birth, it was the King who would decide upon the appropriate match.

Next it is important to understand that these familial and dynastic alliances gave rise to incredibly complex dynamics. We call this half century or so of civil war and murder “The Wars of the Roses”. That was not the name used at the time, when this period of dynastic strife was called – significantly – the Wars of the Cousins. The famous Houses of Lancaster and York were not isolated from each other. They were all from the same small noble elite. They knew each other, they grew up together, they feasted and banqueted together, and they inter married. They also changed sides.

And finally, having stressed that it is the role of these women that we must look to, to really understand the full picture, I have to seemingly contradict myself and introduce some men – but only to set the scene.

First, there are rival kings. Henry VI (b.1421, d.1471), the rather ineffectual Lancastrian candidate, and Edward of York, later Edward IV (b.1442, d.1483), the Yorkist candidate. Henry was middle aged, pious, and prone to mental illness and depression. Richard was young, handsome, vigorous and a noted womaniser. Very broadly, the throne yo-yo-ed between them, with Edward eventually coming out on top, and Henry passed away in mysterious circumstances in the Tower of London. In short, he was murdered.

Edward of York had two brothers. The irritating, power hungry, greedy and feckless George, and the ultra loyal, trustworthy, just and pious Richard of Gloucester, later to become Richard III.

And finally, finally, one other character. The most powerful and richest nobleman in the kingdom, with no direct claim on the throne himself, but one can guess with eyes on the advancement of his family; enter Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick. A man with his own huge private army, and capable of tipping the balance of power with his support, hence the nickname, “Kingmaker”. Although all was not to go quite according to his plan…

Having set the political scene let me try to bring things into more human relief. I am not able nor is it possible to set out the entire dynastic feud between the houses of the red Rose and the White. Suffice to say that this was a mortal feud. The conclusion of this feud and the succession was settled by three women, as much as the men. Who were they? In many respects, they were all surprising candidates.

Anne Neville

Anne Neville had probably the most obvious ticket to high station and power. She was the youngest daughter of the richest and most powerful noble, Warwick the Kingmaker. Warwick must have regarded her, and she must have regarded herself, as a valuable asset, and ready to make a dynastic match which would put the House of Warwick on the throne. And this was, indeed, clearly the plan. Warwick put his money and his men behind the House of Lancaster, and in return the 14 year old Anne was married in France to Henry VI’s 17 year old son, the Prince of Wales. She was therefore Queen in Waiting.

However, when she and her teenage husband landed back in England they received somewhat unexpected and unwelcome news. The Lancastrians had been defeated in battle and her father killed. Her father-in-law Henry VI met his fate in the circumstances I have mentioned, and her teenage husband was left to carry the hopes of the Lancastrian banner. At the Battle of Tewkesbury a few weeks later the Yorkists were decisively victorious. Many Lancastrian leaders fled to seek sanctuary, but Edward of York’s chief enforcer his youngest brother Richard of Gloucester had them all hauled out and summarily beheaded.

Whether her husband died on the battlefield proper or elsewhere I do not know, but die he did, and the House of Lancaster had its entire leadership and all the possible heirs to the throne wiped out. The House of Lancaster had been both literally, and metaphorically, decapitated. All except for the young Henry Tudor, now about 14. As for Anne Neville herself, in a couple of weeks she had fallen from Queen in Waiting to a zero. Her father, father in law and husband were dead, their party defeated, and she was a captive, 14 year old widow, to all intents and purposes an orphan, and with no political future.

Elizabeth Woodville de Grey

Elizabeth Woodville, or Woodville de Grey, had a major problem. She was technically not one of the exclusive club of nobles, although her mother Jacquetta was the daughter of a royal European House of Luxembourg. That in itself has a slight bearing, because it may have given her not simply ambition, but also an air of mystery because that house was reputed to have been descended from a mystical and magical water princess, and stories of witchcraft were to come to dog her reputation.

Notwithstanding some royal ancestry on her mother’s side, she married the much older, stolid, Sir John de Grey, and bore him two children. The de Grey family were staunch Lancastrians. In 1461 her husband Sir John fought for the Lancastrians at the second Battle of St Albans and paid with his life. The Yorkist victory put Edward IV on the throne, and the death of her husband left Elizabeth Woodville de Grey at the age of 23 not only a widow with two small children to bring up, but penniless as she was cut off by a malicious step mother, and tainted by being married into a family which had supported the losing side. She was tarnished goods in many respects. She had no obvious future. She did, however, have talents which were to raise her from a state of impending penury to become one of the three women who would shape the history of Britain.

As was to become more apparent over time, she was plainly hugely intelligent with rare political acumen, courage, loyalty and when necessary, utter ruthlessness in defence of her family. But the most self evident quality which would have struck the casual and immediate observer at that moment in time was her looks. Tall, slender, fair haired, self possessed, she was the epitome of the medieval vision of beauty, and perhaps the most beautiful woman in England.

Margaret Beaufort

In 1456 the Lancastrian King Henry VI was on the thrown and the Lancastrian dynasty seemed secure. Margaret Beaufort, a girl from a well connected noble family had already been promised in marriage when she was one year old. That contract was then torn up, and as a frail young child, aged about 12 was given in marriage to his half half-brother, Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond.

As a twelve year old waif marriage was permissible, but it was not really expected that she would share the marital bed. Even by the standards of the day that was a bit “off”. But Edmund Tudor had no qualms about that, and in January 1457 probably aged no more than 13 she gave birth to a child, a boy. In an age when one in ten women died in childbirth the birth nearly killed them both, and she was never able to have children again.

The boy was named Henry. Just over a year later, her husband died whilst in captivity, and Margaret Tudor, nee Beaufort, was a fifteen year old widow and a single mother in a brutal male dominated world in a ferment of war and intrigue. And what was even more dangerous was that her son, the infant Henry Tudor, had a vestigial claim to the throne via the Lancaster line. I do mean vestigial, but it was there. Which would make him a potential threat to any king.

These three women were then to go on to fight for their future, and the future of their families. I don’t want to give away too much but:

– Anne Neville, the political prisoner, did something which was both shocking and logical. She escaped a form of house arrest and married Edward IV’s chief enforcer and loyal lieutenant, his youngest brother, Richard of Gloucester, the man who had played a leading role on and off the battlefield in the death of her father, her father in law the ex king, and her first husband. In fact, they must have known each other and played together as children, and may well have been genuinely fond of each other anyway. Such were the tangled family relationships of the Cousins’ Wars. But this was also a formidable dynastic alliance, welding two hugely powerful families. Anne was not queen yet. But she must have had eyes on the throne that her father had intended her to have, a throne occupied by her sister in law. A commoner and perhaps a witch.

– Elizabeth Woodville de Grey captured the heart of the new king, Edward IV. Against all convention he married her, a commoner and, second hand goods to boot. This so shocked the conventions of the nobility of the time, so breached social etiquette, that for many there could be only one explanation – she used witchcraft to ensnare him. But she was to become a formidable political animal, and she gave him children. She was willing to destroy any man or woman who threatened their children and inheritance and did so. But in part she failed. Those children ultimately included tshe unfortunate Princes in the Tower. But that was not the end of her or her family’s story.

– Margaret Beaufort sent her son Henry to seek safety abroad, and then became a consummate political animal, marrying into Yorkist families, burying herself deep in the political establishment of the day. A sleeper, always waiting for the chance to advance her son Henry’s claim to the throne, and waiting to strike when the time was right. She did, and killed a king.

Behind the disappearance of the Princes in the Tower lay the power plays and ambitions not just of men, but perhaps principally of these three women. I believe that the fate of the Princes cannot properly be explained without taking into account the role of Margaret Beaufort Tudor, and/or Anne Neville, wife of Richard of Gloucester. Both had good reason to want the Princes dead.

I have probably exhausted everyone’s patience for a Sunday. I may advance a theory on what happened at another date. I commend a watch of Dr Gregory’s series for anyone – it is a master work, an expert who brings dry old papers and boring dates to life. But if there is one thing I would add it is this. I hadn’t quite realised until I started to pen this piece the acute similarities in the circumstances which may have shaped all three women. At an early age all three were widows, two were single mothers too, and all three were in utter peril, whether political or financial. All this in Medieval times, and all that implied. It is no wonder they were to go on to display acumen and ruthlessness. They were forged by their early experiences. No doubt all could play the vulnerable woman as and when called upon to do so. I understand that the writer George R.R. Martin was inspired in part by the “Wars of the Roses” to write his wildly successful Game of Thrones books. All three women could have taught Mr. Martin a thing or too about playing the Game of Thrones. They all played it for real, and put their lives on the line in doing so.

To be concluded in a later post.

Gildas the Monk

August 7, 2013 at 01:34

August 7, 2013 at 01:34

-

Lovely post. I think you’d enjoy “Wolf Hall” and “Bring up the bodies” by

Hilary Mantel – set a little later in history, but intimately connected to

that time.

Both splendid books.

August 6, 2013 at 11:58

August 6, 2013 at 11:58

-

Excellent post , thanks!

I remember reading Sharon Penman’s “A Sunne in

Splendour” many years ago, a novelisation of the Wars of the Roses,

sympathetic to Richard. You have reminded me of the players and the salient

facts; much needed as my head is now filled with GRRM’s world and

characters.

August 4,

August 4,

2013 at 19:01

-

“I have probably exhausted everyone’s patience for a Sunday”

Not so.

August 4, 2013 at 18:06

August 4, 2013 at 18:06

-

“In this world, the country is run by a handful of the elite noble

families”

Remove the word ‘noble’ and replace it with ‘wealthy’ and what’s

changed?

plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose…

August 4, 2013 at 14:44

-

“Henry was middle aged, pious, and prone to mental illness and depression.

Richard was young, handsome, vigorous and a noted womaniser. Very broadly, the

throne yo-yo-ed between them, with Edward eventually coming out on top.”

Is there a typo here?

August 4,

August 4,

2013 at 14:42

-

Thank which I have thoroughly enjoyed reading. It really is a fascinating

and gripping tale. I have been following the White Queen on BBC1 on Sundays

which I am finding difficult although compelling. The BBC drama dept today

seem unable to produce anything without overdone gratuitous sex and violence

and very unnecessary unpleasant images which do not add to the story which to

me demeans it. The Phillipa Gregory series however was a really worthwhile

programme which brought a lot together.

Thank you again Gildas for this great piece of work.

August

August

4, 2013 at 14:37

-

Not bad, not had at all. But there is one important bit missing, the Welles

family. It is not possible to understand Margaret Beaufort entirely without

being aware of this family and their ramifications. Additionally, there are

the complications of the various descents from Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of

Clarence, including that of the Hastings family.

August 4, 2013 at 13:03

-

I do not remember reading Martin, but Rebecca Gablé, I found good.

How accurate, (and the/my origionals appear to have been written in

German.) I do not know. But the whole period is fascinating.

Thanks!

August 4, 2013 at 12:28

August 4, 2013 at 12:28

-

Thank you for directing me to a most enjoyable programme which I might

otherwise have missed (confusing it with the more widely promoted White

Queen). I look forward to the second part.

It is with some shame I am forced to admit that on more than one occasion

my thoughts were directed towards perceived similarities with the fictional,

but completely addictive, Game of Thrones.

August 8, 2013 at 16:41

August 8, 2013 at 16:41

-

No cause for shame that I can see – I believe George RR Martin was

inspired by the rivalry of York and Lancaster when writing the series.

August 4, 2013 at 12:10

August 4, 2013 at 12:10

-

“I have never really “got”, or followed the Wars of the Roses.”

Sigh…obviously you did not read your Ladybird history books diligently

enough at primary school…

August 4, 2013 at 11:26

-

So our present Queenie-Poohs (come back Kenny, all is forgiven) is a direct

descendant of ‘Enry V-one-one , right? I hope tomorrow’s Daily Mail will

SCREAM in righteous CapLock font “ROYAL FAMILY DESCENDED FROM A PEDO”….Perhaps

Operation Hang-Them-From-The-Nearest-Yewtree might like to investigate this

HISTORIC ABUSE claim?

{ 12 comments }