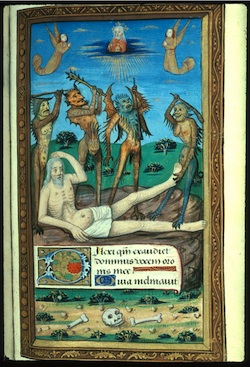

Danse Macabre: The Black Death, Part I

Consider a world in which over the next three months, between 30-50% of the people around you have died of a horrible disease, full of fever and boils, often vomiting blood. What would that be like?

As regular readers will know, from time to time I take a historical topic which I may have heard of, but only have a superficial knowledge, research it and lay the results of my researches before readers of this blog – with our learned editor’s permission. I do not know why. Sometimes I do it for relaxation when I am a bit stressed. Sometimes Raccoon Readers provide their own and learned additional insights.

Last week I decided to investigate The Black Death. It was a disease which wrought havoc in Europe for more than 300 years. In its earliest and most vicious incarnation it killed up to 50% of the population of Europe in a couple of years, perhaps 20 or more million men, women and children. I knew, or I thought I knew, that it was spread by rats and their fleas. I assumed I could provide some salacious and morbidly interesting delicacies with which to titillate the reader. So I bought a couple of books, one being the excellent “The Black Death” by Philip Zieglar (History Press, first published in 1969), donned my notional “Indiana Jones” hat, and headed for the internet. What I did not expect was to discover that most of what I had been told about the disease was probably wrong, and a detective story which would lead to the cutting edge of genetics and the battle against AIDS.

Our editor cautions me about banging on for too long in one piece, so I will write this piece in two parts, beginning with setting out what broadly happened.

In the early 1300’s, possibly about 1320, something very, very nasty awoke on the central steppes of Asia, perhaps in the Gobi desert. Whether there was a draught, an earthquake which caused something to be uncovered which should have been left alone, or a random genetic mutation of a previously harmless bacillus is unknown, and perhaps unknowable. But something happened, something was born or mutated, and people began to die. The Mongol Empire had unified and organised much of the Asiatic word, and opened up trade routes. Following these, inexorably, the terrible disease began to spread through Asia, as well as west.

It must be remembered that this was not a merely European phenomenon. In China, for example, the population dropped from around 125 million to 90 million over the course of the 14th Century.

India was devastated. Mesopotamia, Syria, Armenia, Caramania were struck down. More millions died. Although communications with Asia were poor, rumours began to reach Europe of some strange and horrific catastrophe or nemesis. Tales of fiery rain and an evil noxious mist or cloud that was ravaging the East began to be reported back.

By 1345 the pestilence was on the lower Volga River. By 1346 it was in the Caucasus and in Constantinople. In the same year It hit Alexandria. A thousand people a day were dying there. In Cairo the count was seven times that.

The contemporary Italian writer Gabriel de Mussis records that the plague settled in the Tartar lands of Asia Minor in 1346.

Crimea was an important interface between the Asiatic East and the trading powers of Genoa and Venice, and other Italian city states. At some time in early 1347 in a trading outpost there was a street fight between some Genoese merchants and the local Tartar. This got out of hand, and the Tartars chased the merchants back to their fortified base at Caffa. There the Tartars gathered an army and besieged the Genoese merchants. But as the Tartars waited, they fell sick and began to die. A fearful sickness swept through their camp, decimating them so that the survivors were forced to flee. According to legend, before they left they gave the besieged Genoese a parting gift. The scooped up the rotting bodies of the dead and used their siege catapults to fire them in great numbers over the walls of the fortress, poisoning the air and the water supply in what may have been the world’s first act of calculated germ warfare.

It may be the story of flinging the dead over the walls is apocryphal. Be that as it may, the Genoese fled in their ships, heading for the “safety” of the Italian peninsular. What happened next is most assuredly not apocryphal. The ships headed for the port of Messina, on Sicily. When they arrived, the locals found them full of corpses and dying sailors. This is a contemporary account:

“At the beginning of October, in the year of the incarnation of the Son of God 1347, twelve Genoese galleys . . . entered the harbor of Messina. In their bones they bore so virulent a disease that anyone who only spoke to them was seized by a mortal illness and in no manner could evade death. The infection spread to everyone who had any contact with the diseased. Those infected felt themselves penetrated by a pain throughout their whole bodies and, so to say, undermined. Then there developed on the thighs or upper arms a boil about the size of a lentil which the people called “burn boil”. This infected the whole body, and penetrated it so that the patient violently vomited blood. This vomiting of blood continued without intermission for three days, there being no means of healing it, and then the patient expired.”

This description may be very important in understanding what the disease was or was not, for reasons I will explain on another occasion. It continues:

“Not only all those who had speech with them died, but also those who had touched or used any of their things. When the inhabitants of Messina discovered that this sudden death emanated from the Genoese ships they hurriedly ordered them out of the harbor and town. But the evil remained and caused a fearful outbreak of death. Soon men hated each other so much that if a son was attacked by the disease his father would not tend him. If, in spite of all, he dared to approach him, he was immediately infected and was bound to die within three days. Nor was this all; all those dwelling in the same house with him, even the cats and other domestic animals, followed him in death. As the number of deaths increased in Messina many desired to confess their sins to the priests and to draw up their last will and testament. But ecclesiastics, lawyers and notaries refused to enter the houses of the diseased.”

Understandably, the terrified citizens of Messina fled the town and dispersed across Sicily. But they took the pestilence with them. Whole towns and villages were wiped out. By the new year the pestilence had reached the Italian mainland.

In Sienna, a local merchant, shoe maker and sometime public official called Agnolo di Tura kept a diary of what was going on. He recorded this:

“The mortality in Siena began in May. It was a cruel and horrible thing. . . . It seemed that almost everyone became stupefied seeing the pain. It is impossible for the human tongue to recount the awful truth. Indeed, one who did not see such horribleness can be called blessed. The victims died almost immediately. They would swell beneath the armpits and in the groin, and fall over while talking. Father abandoned child, wife husband, one brother another; for this illness seemed to strike through breath and sight. And so they died. None could be found to bury the dead for money or friendship. Members of a household brought their dead to a ditch as best they could, without priest, without divine offices. In many places in Siena great pits were dug and piled deep with the multitude of dead. And they died by the hundreds, both day and night, and all were thrown in those ditches and covered with earth. And as soon as those ditches were filled, more were dug. I, Agnolo di Tura . . . buried my five children with my own hands. . . . And so many died that all believed it was the end of the world.”

Again, there is something extraordinary interesting, as well as sad, about what Agnolo writes. It actually struck me when I first heard his account and before I did some more research. He buried all five of his children. But why did he survive unscathed? In fact, this has curious parallels with the events which were to take place in the sleepy Derbyshire village of Eyam, more than 200 years later. Elizabeth Hancock, beloved wife and mother, buried her six children and husband in the space of less than a month. And yet she remained unscathed. Again, how and why? Luck? Or something more much more significant?

But I digress. The pestilence now raged across Italy and into the rest of Europe. In Venice, 90,000 died. In Marseille, half the population within two or three months. In Avignon 11, 000 were buried in six weeks.

In Florence, 75% of the population died. One of the citizens of Florence was a writer and philosopher called Giovanni Boccaccio. He was to go on to write a book of morality tales based on the pestilence called “The Decamaron”. The book was widely circulated and contained what became one of the best known (though possibly misleading!) descriptions of the symptoms of the disease:

“The first signs of the plague were swelling in the groin or armpits. These bulges ranged between the size of an apple and an egg. They were called gavoccioli. Soon after contracting the plague the gavoccioli would spread over the whole body. The next stage of the disease was black or livid spots on the arms and thighs, spreading over the rest of the body in a short time. Nothing could be done, most died within three days, only a few were ever cured. The pestilence passed from the sick to the healthy, being around a sick person in any way including touching their clothing could make you sick. I (the narrator) saw it with my own eyes. Animals even died from the pestilence.”

The pestilence moved with incredible speed for a world without cars, trains or aeroplanes. In less than a year it had devoured and traversed Europe. By the summer of 1348 it had reached the coast of France.

There are quite a few places that claim the “honour” of being the first place in England to welcome the infection. Bristol is one candidate, but there are others. A Grey Friar wrote this:

“In this year 1348, in Melcombe, in the county of Dorset, a little before the Feast of St John the Baptist, two ships, one of them from Bristol, came along side. One of the sailors had brought with him from Gascony the seeds of terrible pestilence and, through him, the men of the town of Melcombe were the first to be infected”.

Such was the virulence of the pestilence, it does not matter where it landed first. It was inexorable.

By November it was in London, and the carnage was appalling. Death pits such as those that have been excavated at East Smithfield were filled with thousands of bodies. Between one third and one half of the population of died within six months. One skeleton now in the British museum is a sad and grisly indication of how great the chaos was. It is the upper portion of a woman. There is nothing below the rib cage, but no sign of violence. The reasonable hypothesis is that her corpse had rotted for so long that when she came to be picked up, the body literally fell apart. The authorities were struggling to cope with “King Death”.

Throughout 1349 the plague raged throughout the rest of England, and then carried on through Scotland and up to the Baltic. It was then to seemingly vanish, only to re appear a few years later and crop up sporadically for the next 300 years.

What was the cause of this pestilence? Does it still exist, or is there a modern counterpart? How did it spread? Why was it so virulent?

From about 1860 a plague began to spread across South East Asia. In 1894 it arrived in Hong Kong. The symptoms included raging fever, coughing, and the eruption of swollen lymph nodes in the groin, armpits and neck – so called “buboes” – delirium, and death within a few days.

A brilliant young Swiss scientist called Alexander Yersin was determined to identify the cause of the plague, even though the British authorities resented it and tried to stop him. Illegally, he obtained access to the dead and started dissecting the buboes on the still rotting bodies. He discovered that the cause of the infection was the so called “Yersinia Pestis” or “Y Pestis” bacterium. It plainly attacked the lymph nodes (which are the body’s control centre for fighting infection, causing the swelling or “buboes”). The cause of so called “Bubonic” Plague, if not the means of abating it, had been explained.

But the mechanism of infection still remained unexplained. By 1898 the Plague had reached India. No one could stem it because the mechanism of infection was unknown. In Karachi, one of Yersin’s students called Paul-Louise Simond noticed the numbers of rats dying in the street. He also noticed flea bites on the bodies of the afflicted. He sensed a connection, and discovered that the Y Pestis bacterium could be found in the stomach’s of the rat fleas. He then risked his own life by catching a plague infected rat and conducting an experiment which proved that infected rats spread the plague. When the rats died, the fleas sought a new home and something new to eat. If that had to be a human, so be it. In the rat flea, the bacterium multiplies in the flea’s stomach causing congestion. When the flea wants to feed it regurgitates the stomach contents into the host’s blood stream, and the bacillus is passed on with fatal results.

At the time the scientific press was quick to draw a correlation between Bubonic Plague and the Black Death, and ever since it has been assumed that the cause of the epidemic – and the Black Death – is explained in the form of Bubonic Plague. In fact, there are at least three forms of Plague.

Bubonic Plague itself. Due to its bite-based form of infection, the bubonic plague is often the first step of a progressive series of illnesses. Bubonic plague symptoms appear suddenly, usually 2–5 days after exposure to the bacteria. Symptoms include:

- • Acral gangrene: Gangrene of the extremities such as toes, fingers, lips and tip of the nose.[5]

- • Chills

- • General ill feeling (malaise)

- • High fever (39 °Celsius; 102 °Fahrenheit)

- • Muscle Cramps[6]

- • Seizures

- • Smooth, painful lymph gland swelling called a buboe, commonly found in the groin, but may occur in the armpits or neck, most often at the site of the initial infection (bite or scratch)

- • Pain may occur in the area before the swelling appears

- • Skin color changes to a pink hue in some very extreme cases

Another form is Pneumonic Plague, passed by coughing and a lung infection caused by the primary Bubonic form. The third manifestation is Septicemic Plague. This sickness would befall when the contagion poisoned the victim’s bloodstream. Victims of Septicemic Plague died the most swiftly, often before any notable symptoms had a chance to develop. Another form, Enteric Plague, attacked the victim’s digestive system.

Looking at these strains of Bubonic Plague and the symptoms desrcribed above, it would be easy to come to the conclusion that the Black Death was shorthand for all these strains, or perhaps as hybrid form of the Plague. In fact a combination of historical research, statistics, and understanding of how Bubonic Plague is spread now strongly suggests that the Black Death was not Bubonic Plague at all, or at least not as presently in existence, but something even more deadly, and that rats had nothing to do with it. Medieval man may have had very little scientific understanding, but just looking at the accounts I have set out above, it is quite striking how they stress personal contact as being a factor in transmission. And there is that puzzling feature I mentioned above. If the plague was so virulent, how can a man in 14th Century Italy and a woman in 17th Century England both be exposed, bury all their families and yet suffer no ill effects?

In another blog I shall try to explain why the commonly taught notions about what the Black Death was and how it was transmitted have now been overturned. And how the actions the actions of a 17th Century Derbyshire village throw light on the genetic history of Europe, and the fight against AIDS.

Gildas the Monk

December 10, 2012 at 20:08

December 10, 2012 at 20:08

-

For those Raccoon habitues impatient to know more, reading Daniel Defoe’s

fictional version of the last time the plague overtook London, “Journal of a

Plague Year” may entertain while waiting for Gildas to produce his next ration

of disease and death. It’s a great read ( and reread).

December 10, 2012 at 11:51

-

Part 2 is nearly done everyone – but I am awaiting a copy of the book

Odin’s Raven kindly recommended. That should arrive tomorrow. Meanwhile I am

struggleing on manfully with the reconstruted DNA of Y pestis!

I have also

been set a new challenge by a reader – The Man in the Iron Mask!!! can anyone

tell me where to start!

December 10, 2012 at 12:01

-

Chez Raccoon might be a good place. Or was that the idea. If you know

what I mean.

December 10, 2012 at 13:02

December 10, 2012 at 13:02

-

You could kick off with ‘Who was the Man in the Iron Mask’ by Hugh Ross

Williamson; despite the title, he only gives it 14 pages in a collection of

20 historical mysteries – the usual Amy Robsart, sir Thomas Overbury and the

Princes in the Tower plus some less well known ones – but you might find

some pointers, though, unfortunately he doesn’t include a bibliography.

December 10, 2012 at 11:33

December 10, 2012 at 11:33

-

Fascinating and well researched ! Interestingly, the ‘Christmas Special’

Family Tree magazine has a free cd with e books in it. One is ‘the Brave Men

of Eyam’. I’ve yet to look at it. Hurry up and post part 2 !

December 10, 2012 at 10:39

-

Hope raccoons don’t attack marmots or at least not the lymph gland under

the armpit

where the soul of a dead hunter lives.

December 10, 2012 at 04:46

-

God. I hope we haven’t got to wait till next week for Part ll. I’ve got a

Flea Bite so I could be dead by then.

December 9, 2012 at 21:40

December 9, 2012 at 21:40

-

Could Anna possibly add a new tab at the top for these historical works by

young Gildas? There are great little introduction’s to topics I haven’t yet

studied myself. I’d hate to miss any.

December 9, 2012 at 20:36

December 9, 2012 at 20:36

-

Well written. I’ve visited Eyam and it’s quite a sombre experience, seeing

how the plague spread through the village decimating families and the

sacrifice made by the villagers to prevent the spread of the disease.

December 9, 2012 at 20:35

December 9, 2012 at 20:35

-

‘…The Black Death’:

Death…

Carnage…

Rotting Corpses…

Terror…

A suitably Christmassy subject…. Except that in 2012 we still have all

those things going on in the world right now, from a myriad of sources.

December

December

9, 2012 at 19:04

-

Been looking forward to this all day and saving it up until I had leisure

to read – it was well worth the wait!

(Tangentially, for the general context of the 14th-century outbreak in

Western Europe, it’s hard to beat Barbara Tuchman’s ‘A Distant Mirror’.)

December 10, 2012 at 09:25

-

I was going to recommend that; it has the virtue of telling a tale

plainly, as opposed to many of the sources employed. The Chronicles of

Froissart are interesting, but the reader will suffer from the great slabs

of indigestible translation from years past. But the strapline – ‘The

Calamitous Fourteenth Century’ – does, for once, describe it well.

But I am always moved, when reading of these tragedies, at the

willingness of people (particularly, but not exclusively, the clergy) to put

themselves in harm’s way in full knowledge of what might befall them, with

absolutely no way back.

December 9, 2012 at 18:30

December 9, 2012 at 18:30

-

Booking my ticket for the sequel.

December 9, 2012 at 18:30

December 9, 2012 at 18:30

-

Good article. I dug out my copy of “In the Wake of the Plague” by Norman F.

Cantor to have a quick scrutiny so I will post no spoilers. Is this one of the

books you researched for your posts?

December 9, 2012 at 17:26

December 9, 2012 at 17:26

December 9, 2012 at 17:14

December 9, 2012 at 17:14

-

Very good stuff, Gildas. Look forward to the next installment.

December 9, 2012 at 16:52

December 9, 2012 at 16:52

-

I’d really like to know what ‘sources’ Kipling used for his plague story-

written for children – “A Doctor of Medicine”(Rewards and

Fairies,1910).

This features the ‘herbalist’ Nicholas Culpepper, so is

presumably related to an outbreak in mid 17c?

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/556/556-h/556-h.htm#2H_4_0032

December 9, 2012 at 14:47

December 9, 2012 at 14:47

-

Thanks for the post, I look forward to the next installment.

December 9, 2012 at 13:44

December 9, 2012 at 13:44

-

Very well written, interesting piece Sir. I too look forward to the next

instalment! Hurry up please.

December 9, 2012 at 13:09

December 9, 2012 at 13:09

-

Here’s the link for anyone who wants to see some more while waiting for

Gildas The Monk next episode:

http://kat.ph/secrets-of-the-dead-mystery-of-the-black-death-digitaldistractions-t594804.html

If

unable to get it up due to big brother legislation, let me know and I’ll

upload it to my DropBox for public access.

Looks like this Secrets of the

Dead series has some interesting stuff…

December 9, 2012 at 13:31

December 9, 2012 at 13:31

-

If unable to get it up due to big brother legislation

I’ve tried that excuse, but she never believes me.

December 9, 2012 at 13:50

December 9, 2012 at 13:50

-

My apologies Mr. Monk, didn’t mean to do an Imdb, just got caught up in a

Sunday afternoon Black Plague roll on the Web!

December 9, 2012 at 14:45

-

LOL!

December 9, 2012 at 12:41

December 9, 2012 at 12:41

-

Oh, now I’m really annoyed because I’m itching to read the next part. Hope

it won’t be too long before it’s posted

December 9, 2012 at 12:33

December 9, 2012 at 12:33

-

This is a fascinating and tantilising entree and I cannot wait for the next

course.

keep it up Mr Monk Sir

December 9,

December 9,

2012 at 12:16

-

Great post yet again Gildas.

Regarding that part skeleton of a woman, I have a possible explanation: you

wrote “Between one third and one half of the population of died within six

months”. Perhaps she was half dead – I’ve had flu that felt like that.

December 9, 2012 at 12:22

December 9, 2012 at 12:22

-

If her bottom half continued on, she stood a good chance of a happier

life. She would not have got headaches that’s for sure. Heck, I hope the

husband stayed around talking about silver linings to his mates in the

pub.

December 9, 2012 at 12:39

December 9, 2012 at 12:39

-

Certainly sounds preferable to the desired tyrannical impositions of

many now parading about, whose half death seems to have been confined to

the parts between neck and knee

December 9, 2012 at 12:01

December 9, 2012 at 12:01

-

It’s fiction but I found the Doomsday Book by Connie Willis an

unforgettable read.

http://www.tor.com/blogs/2012/06/time-travel-and-the-black-death-connie-williss-doomsday-book

December 9, 2012 at 11:56

-

There’s an excellent website with lots of quite technical work on matters

pestilential to be found here for those with a desire to learn more.

http://bldeathnet.hypotheses.org/

This is a good article on the DNA evidence found at East Smithfield

regarding Yersinia Pestis.

http://contagions.wordpress.com/2011/10/16/black-death-genome-fished-out-of-east-smithfield/

December 9, 2012 at 13:01

December 9, 2012 at 13:01

-

No vaccination against the plague but according to Dr. Stephen O’Brien,

if you have the CNN5-delta 2 genetic mutation it can’t enter your

system:

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/secrets/previous_seasons/case_plague/interview.html

This

American pbs.org channel appears to have made a series called Secrets of the

Dead with several episodes on case file: ‘Mysteries of the Black Death’.

Will check and see if they’re available on kat.ph- my favourite source of

freebee downloads, still available in Spain despite much-discussed

legislation!

December 9, 2012 at 13:25

-

Yep, this is where I am goind with this! No moreplot spoilers

please!

December 9, 2012 at 11:13

December 9, 2012 at 11:13

-

Fascinating reading and I await with bated breath for the second part along

with the scientific theories as to why some people are immune to such

devastating plagues.

Fortunately, outbreaks of Ebola in some African countries appear to have

been kept under control so hopefully, should any psycho decide to let loose

their stock of germ warfare on their ‘enemies,’ today, the spread could be

rapidly contained, airborne diseases being a different matter of course.

December 9, 2012 at 11:10

December 9, 2012 at 11:10

-

Why, oh why, were History Lessons at school never so interesting &

enthralling?

Thank you Gildas for sharing your research.

Roll on next week!

December 9, 2012 at 21:25

-

Very valid point, Joe. History IS interesting and enthralling, it’s all

about the delivery. Most History Lessons at school seemingly sought to

eliminate any hint of those qualities, thus rendering it a turgid ramble

through irrelevances.

If you were ever fortunate to have an inspiring

history teacher, as I did for the Industrial Revolution period, it all comes

alive and even now, almost half a century later, as I observe the local

post-industrial landscape of canals, railways and mills, I link back

immediately to those founding lessons, enabling me to put everything in its

place and context, adding living colour to an otherwise degrading scene. But

no other teacher of other historical periods achieved that vibrancy, so

those other eras remain vague and disconnected.

I applaud Gildas, not only for the quality and depth of the research, but

also for delivering the output in such a human and readable form – if only

the nation’s current crop of history teachers were compelled to read Gildas,

maybe the next generations would then have more appreciation of how we came

to be what and where we are.

December 9, 2012 at 11:08

-

I think this may be the book with the real explanation.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Return-Black-Death-Worlds-Greatest/dp/0470090006

December 9, 2012 at 11:44

-

I havent read that OR, but a quick persusal suggests that I will be going

down the same path and reaching the same conclusions….

December 9, 2012 at 19:54

-

I have just ordered it!

December 9, 2012 at 10:11

-

A well researched peice Gildas,

May I recomend to you Barney Sloane’s “The Black Death in London”. He’s

looked at the wills and hustings rolls drawn up in London in the terrible year

1348/49 and extrapolated death rates for London from these. His conclusion is

that 55-60% of a population of about 60’000 were carried off in 7 or 8 months.

There was no one, or at least no one who survived chronicling the pestilence

in London so the wills give an at times heart rending account of what it must

have been like for the citizens. Fathers and mothers, who most likely drew

their wills up as they were suffering the first agonies of the pestilance

themselves leaving their worldly goods indeed entrusting their children to

relatives only for the relatives to die and even all the executors of wills to

be laid low. Some of the children were left literally on thier own with

nothing or taken under the care of the church. The church itself suffered

appalingly.

He also touches briefly on the nature of the disease although that’s not

what his study is primarily about. The majority of the wills were drawn up

between December and April, a time when it’s thought that the activity of

fleas would be lowered due to cold weather. It appears that the disease had

become pneumonic by this stage and in a tightly packed city of London still

contained within it’s defensive walls the stage was set for catastrophe.

The pestilance and it’s affects on society in it’s aftermath are a

fascinating area of study.

I look forward to your next piece.

December 9, 2012 at 11:42

-

That is the thing about Raccoon Readers! What they know is amazing! Thank

you!

December 9, 2012 at 14:05

December 9, 2012 at 14:05

-

Another bit of reading that may give some insight into how the Plague

affected ordinary folk is Michael Wood’s very readable ‘The Story of

England’, English history told through the perspective of one village,

Kibworth, and it’s inhabitants from the time of it’s foundation in the Dark

Ages. The chapter on the arrival of the Plague, and it’s effects on the life

of the village is most vivid. There remains to this day an entry in the

Parish records in which the Vicar leaves a message for any of mankind who

might survive, he believing at the time that the whole population would

succumb. A terrifying time indeed; and not just one event – outbreaks

continued until about 1420, and less frequently in later centuries.

December 9, 2012 at 14:48

-

Quite so! I saw some of the episodes, but I dont have that book. It was

Mr Wood who first got me interested in early history, with his classic In

Search Of….” Series. Which can still be found in various bits and bobs on

Youtube..

December 9, 2012 at 09:30

-

You have captured my interest

December 9, 2012 at 09:16

December 9, 2012 at 09:16

-

Great post – looking forward to Part 2!

December 9, 2012 at 09:13

December 9, 2012 at 09:13

-

Oooooh, Goody. The Monk is on the trail. Go get’em Gildas.

{ 51 comments }